Join us as we travel across England visiting well-known wonders and some lesser-known places on your doorstep - all of which have helped make this country what it is today.

100 Places Podcast #24: Tragedy and the Fight for Justice

This is a transcript of episode 24 of our podcast series A History of England in 100 Places. Join Dr Suzannah Lipscomb, Dan Cruickshank, Emily Gee and Professor Phil Scraton as we continue our journey through the history of loss and destruction in England.

A History of England in 100 Places is sponsored by Ecclesiastical

Voiceover:

This is a Historic England podcast sponsored by Ecclesiastical Insurance Group.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

Hello, I'm Dr Suzannah Lipscomb and you're listening to Irreplaceable: A History of England in 100 places. In this series we explore the 100 places that help tell the story of England. If you are enjoying the series don't forget to subscribe so you don't miss an episode. And if you are listening on iTunes, please rate this podcast and leave a very nice review.

Today we have just three more locations to explore in the Loss & Destruction category, which is judged by Professor Mary Beard. The category has been about exploring the ten most striking examples of places that have been lost or destroyed, or those that have been witness to loss and destruction.

The three places we will be looking at today, with the help of my studio guests, historian Dan Cruickshank and Historic England's Emma Gee, take us into some recent and painful events. These places have been the sites of terrible tragedies and for better or worse they have shaped us as a nation. They have taught us how to confront the past and make progress from what we've learnt.

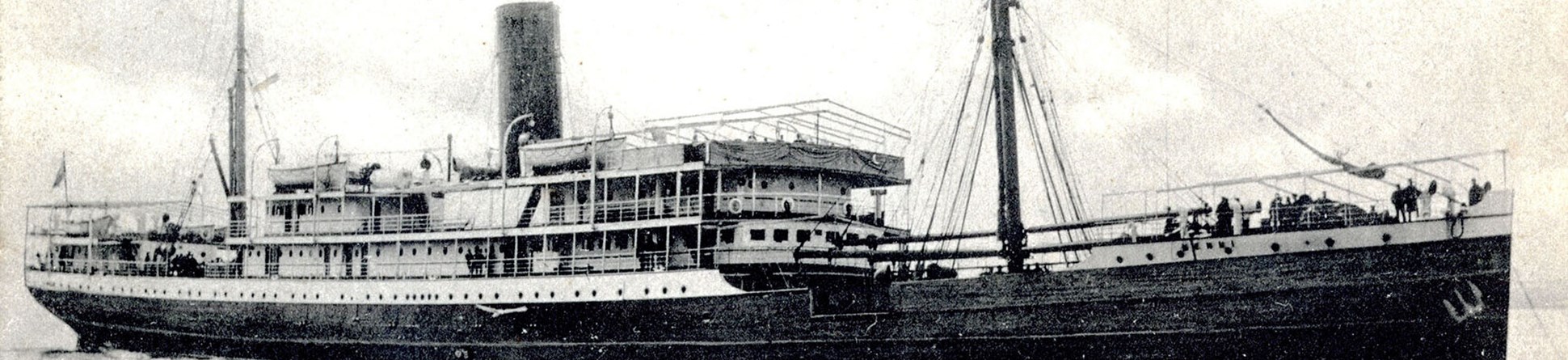

We begin with the wreck of the SS Mendi, a steamship built in 1905 and lost at sea 21 kilometres off the Isle of Wight in 1917. Our category judge Mary Beard said that this point out at sea is important because of the "then unseen nature" of the lives that were lost in the tragic event which occurred here. So, what happened?

Emily Gee:

The Mendi was a Liverpool steamship which was brought into wartime service by the British government in 1916 and she was carrying 823 South African servicemen to Europe from Cape Town. The First World War had brought a huge labour gap and it was really important to bring in troops from around the Empire- subjects were drafted in to assist in a wide range of roles on the front line. The Mendi was bound from Cape Town and she was heading to France, the Western Front, and disaster struck on the 21st of February 1917.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

Was she shot down, was it a U boat accident?

Emily Gee:

No, and of course that was the biggest threat, but that wasn't the case. It was fog and it was a devastating accident really. The Mendi slowed down to cross the Channel and another steamer twice its size, the Darro, plunged into the side of the Mendi. We know it cut the hull directly in half. We found later that the Darro had been travelling much too fast and hadn't been using fog signals correctly.

Sadly, the ship also offered no assistance and the lifeboats had been made unusable by the hit. Hundreds of crew and servicemen died.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

Hundreds of lives were lost then?

Emily Gee:

Yes, hundreds. And these were men from the South African Native Labour Corps- there were 618 black South Africans who were killed and many of them had never seen the sea before. There were also 33 crew and a number of white officers and military personnel were also killed. The ship sank in just 25 minutes, it was really devastating. We know in South Africa from oral traditions - there is a really strong sense of community about this devastating moment - and it recounts the story, it's really quite remarkable and deeply emotional.

The Reverend Isaac Wauchope Dyaobha, who was on board the ship at the time, and amazing- he came and addressed these men who knew they were about to die and he sought to calm them and fortify them at this devastating moment. And we know he said some really powerful words, he said: "be quiet and calm my countrymen…You are going to die, but that is what you came to do…we die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa".

Amazingly, he led them in a barefoot dance, a death drill- we know that they were singing and drumming their feet on the decks of the ship together in a great sense of solidarity as she went down.

Dan Cruickshank:

Because they could not swim and the lifeboats had been destroyed, that's why they were in this terrible situation.

Emily Gee:

Some men were saved. Another ship came - it wasn't the Darro that rescued survivors - another ship was there and took some of them away and there were some survivors, and it led to long court cases.

Dan Cruickshank:

There was a charge: there was some racial aspect of the rescue not being effective or timely. It is brutal and horrible to contemplate but presumably this is part of the story which we have to face up to. How was that taken at the time, was that charge taken seriously?

Emily Gee:

The reason that the Darro never helped was never fully explained. There was plenty of room on the ship to have rescued survivors and the ship itself sustained comparatively little damage- it was much, much bigger. It was the HMS Brisk that actually carried those few survivors to safety. The Captain of the Darro, some say he lost his nerve, others as you say, there was charge that it was racially charged response at the time.

We just don't know- we can speculate about the reasons behind it, but we know he was held to account for a short period of time, lost his licence for having failed to stop properly in the mist, but there was nothing to the reflect the extraordinary, devastating loss of life.

Dan Cruickshank:

I suppose one thing is to see how this was commemorated at the time, how it was explained at the time. There are memorials in South Africa and here, how was it actually explained?

Suzannah Lipscomb:

That's one thing that strikes me as well, we know about the Mary Rose nearly 500 years after that sank, but this is little known, isn't it? The Mendi, why don't we know more about this, why has it been forgotten?

Emily Gee:

The story is well known in South Africa, it has been passed down from generation to generation. The black community has a deep sense of loss and memory of this event. During the years of Apartheid, the ship in a way became a symbol of the injustice faced by black South Africans. But as you say the story hasn't been well known in England. But in the last few years there has been a great awakening leading up to the centenary of it; there is much greater discussion. Historic England has produced some wonderful curriculum guides for school children- there is an act of memory now.

The South African Prime Minister at the time, he thanked the Labour Corps for their loyalty to flag and King. But none of the South African Native Labour Corps were actually commemorated with medals at the time, although the white officers were.

Dan Cruickshank:

Is there a statue or memorial? If not one should be made immediately, shouldn't it? There are memorials on the south coast I believe.

Emily Gee:

There are a few ways in which it is remembered. In 2003, the Mendi gave its name to South Africa's highest award for courage, which is the Order of the Mendi Decoration for Bravery and it is bestowed by the President on the country citizens. There is also an interpretation plaque on the south coast- a point at which one can stand and look out to where the scene of the wreck was. The wreck was discovered in 1974, and known to be the Mendi, some items were taken from it and brought up.

The ship still sits there and the Ministry of Defence has protected the wreck. It is designated as a protected place under the protection of the Military Remains Act in 1986, so it is a military maritime grave.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

This is a really shocking story, but it reminds us of the very important role played by people across the Empire, both in combatant and non-combatant roles in the war, but also that this loss can be passed over in such a way. So I think it is extremely important that the location and its loss is recognised and remembered. I'm very glad it is part of this list.

Emily Gee:

Shortly after the disaster, some of the bodies washed ashore and a few of the men are buried in England. I think 12 of them are buried here; one is buried in France; there is a memorial in Holland. There is a wealth of information in published form to try and capture some of this sad and important moment in history.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

It is possible to find out more about this and maybe we look into ways that they can be commemorated more.

We more now to our ninth location, which also has a shocking story to tell. This episode is all full of difficult things, I'm afraid. The Neepsend district in Sheffield is where the river Don surges through. It is overlooked by a well-known Sheffield landmark, the Neepsend gas Works, which opened in 1852. The gas holder here no longer operates, but it stores North Sea gas and it sits at location number nine on Mary Beard's list: The Farfield Inn, which was once known as the Owl. This is a rather humble looking little building. It looks forgotten, but it is Grade II listed, which indicates its significance. So, what is special about this place?

Emily Gee:

The reason this inn features in this category is because it was witness to one of the biggest manmade disasters in English history, which has largely been forgotten. It was in 1864 on March the 11th when the dale dyke damn burst and 650 million gallons of water inundated the Locksley and Don Valley of Sheffield, killing at least 250 people.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

It is known, isn't it, as the great flood of Sheffield. But what caused it, do we know?

Emily Gee:

The Sheffield Waterworks Company had constructed and nearly finished the first of several dams they planned in the area in 1864. The idea was that several reservoirs would be created as part of this. The dam was full and the embankment was just getting its finishing touches on it, when on the way home one night, one of the local workers noticed a crack. The Chief Engineer was summoned and thought it was just a surface crack. Nevertheless, they worked through the night to try and drain a bit of the water, because it was a very wet night.

It was in vain because shortly afterwards, part of the dam collapsed and that's what released these millions of gallons of water through the valley down towards Sheffield, where hundreds of people were asleep in their homes.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

That's extraordinary because it would have done such damage so quickly. If you think about that volume of water, 250 people, at least, died.

Dan Cruickshank:

400 houses washed away, 20 bridges. But the inn survived, miraculously. What a weird story this is…

Suzannah Lipscomb:

The inn which was built in 1752 or '53, miraculously stood. There is a picture of the three-storey stone building standing stoically looking over the destruction in the wake of the flood.

Dan Cruickshank:

There was an inquiry and presumably this was a private water company and they cut corners in location or something. There must have been lessons learnt and applied- the world must have changed in this country after this.

Emily Gee:

There was an inquest after the event and at the time there were all sorts of theories as to why it had collapsed. But it largely pointed to poor design and workmanship on behalf of the company. The others were meant to be really well built, so it just seemed to be an issue with this particular dam.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

That's what Mary Beard, our judge, said about it: she said the lasting reform and assessment of corporate responsibility was an inevitable result of this tragedy. It is from examples like this that one learns, I mean these are terrible examples…

Dan Cruickshank:

It is interesting because you have to look at the railway companies and the famous bridge collapses of this period. Again, often poor design or skimpy execution or poor materials- it's all part of that world, the Victorian world of private companies rushing here for profits, but they would cut corners.

Emily Gee:

There was massive public interest around it at the time: newspapers were asking all sorts of questions of accountability and organising a public response to the destruction. It really captured the public imagination about accountability of major public companies.

Dan Cruickshank:

I know Sheffield very well- I love it, I've worked up there, but I haven't been to the site. What's on the site now?

Suzannah Lipscomb:

There is a bridge now, the original bridge was lost at the time. The other point I wanted to note is that this is still very much a contemporary debate about how you regulate public amenities, how you make sure this doesn't happen again. This is very topical, isn't it?

The uncomfortable observation to make here, although there were many accounts of blame, no single body or company was held responsible for the disaster and its impact on public life.

Dan Cruickshank:

Therefore, no compensation was paid to the families of the 400 or so?

Suzannah Lipscomb:

Not that I know of.

Dan Cruickshank:

Gosh, it was another world wasn't it? Ruthless Victorian world of commerce and thrusting…

Emily Gee:

And there stands the pub reminding us…

Suzannah Lipscomb:

Our tenth and final location in the Loss & Destruction category, selected by Professor Mary Beard, is the Hillsborough Football Stadium in Sheffield, nominated by you. In her words she says, "this place is a powerful symbol of human tenacity in the pursuit of justice after a terrible loss of life".

As you probably all know, the Hillsborough Disaster occurred on the 15th of April 1989, during the 1988-89 FA Cup semi final game between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest. Shortly before kick-off, in an attempt to ease overcrowding outside the entrance turnstiles, the police Match Commander ordered exit gate C to be opened, leading to a rush of supporters in the already overcrowded standing only central pens allocated to Liverpool supporters.

This decision resulted in the worst sporting disaster in British history, causing the death of 96 Liverpool football fans and leaving 766 people with both physical and mental injuries. Following a campaign for justice by various groups and individuals, hard fought for years, in 2016 a Coroner's inquest ruled that the supporters were unlawfully killed. Crucially the Inquest concluded that the behaviour of the supports themselves was not to blame for the disaster.

The campaign for justice in the aftermath of the tragedy continues in the hope that the families of those who lost their lives can find some resolution and peace. Let's hear more.

Phil Scraton:

I'm Professor Phil Scraton, I'm professor in the school of law at Queens University Belfast.

In the immediate aftermath of Hillsborough, it was obvious to me that there needed to be an independent form of investigation. The Inquest verdict was accidental death and what we were able to demonstrate from our research was that, far from it being an accident, Hillsborough was the product of deep institutionalised negligence that had occurred over many years, both in terms of the condition of the stadium, but also in the way the stadium was policed, the way entry and egress was conducted into and from the stadium, and also, a general view that was held by the authorities that they were dealing with fans who would be troublesome, as opposed to focusing on safety. Fans were penned in, both to the side and to the front with high, spiked fences: very limited potential for getting out of those pens if there was a disaster. The access to the two central pens, where people died at Hillsborough, was down a one in six gradient tunnel, which was illegal.

In opening that exit gate, but not sealing off the tunnel, it meant that fans not familiar with the ground went down this one in six gradient tunnel into the backs of the already full pens. They couldn't come back up, the fans at the front couldn't get out, so a crush evolved which led to the breaking of a safety barrier at the front where the fans were piled high, and that's where they died.

The way in which that was immediately reported was that Liverpool fans had rushed the stadium, that they had caused the deaths of their fellow fans. And in actual fact it was then published that they were drunk, they were out of control, they were violent, and many hadn't got tickets. This fitted a narrative that was well established by this time around crowd violence and football-related hooliganism.

That was the lens through which the Public Inquiries began to view Hillsborough. The decision was taken by the jury that the deaths were accidental. I think that then set a tone all the way through the further investigations, the appeals, at every level we came back to the same issue. And it was in 2009 when Andy Burnham made a pledge in a packed stadium at Anfield: he made a commitment that evening to a new investigation. The Hillsborough Independent Panel was set up, I headed the research on the panel.

We were able to demonstrate that the Inquest had failed, that even Lord Justice Taylor's report had failed, that all of the previous processes failed to demonstrate the truth of Hillsborough. We had 153 clear findings: we exonerated the fans and we laid the responsibility at the doors of all the institutions involved. And as a consequence of that, the new Inquests were then ordered, the previous verdicts of accidental death were quashed, a full independent police complaints commission inquiry began, which is still ongoing after all this years, as did a criminal investigation, which has led to the prosecution of six people involved with Hillsborough.

I was walking through Liverpool the day after the report came out and a guy came running towards me and threw his arms around me, and he just said "I'm a survivor from Hillsborough and today is the first day I could walk through the city with my head held high". The city had been vilified, its people had been vilified. And let's remember that the Inquest verdicts were unlawfully killed, all 96 who died had been killed unlawfully.

It changed overnight people's perceptions and understanding. It didn't give me any pleasure to say "I told you so", because I had witnessed the suffering and premature death of so many family members, so many survivors who had gone through hell at Hillsborough and then had lived hell afterwards. It is so important not to see Hillsborough as a football tragedy, as a soccer tragedy, but to see it as a moment in our lives when we witnessed, on a large scale, the deaths of people who were out enjoying themselves.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

The stadium witnessed a terrible event in our collective history and it's an interesting decision that rather than demolishing it, the stadium has continued to be used. What do you think about that?

Emily Gee:

In many ways the continued use of the building as a football stadium stands a living memorial, as a reminder of sport and how that brings communities together often, unites us a people, as a country. It's the idea that it's a memorial to the people who died watching a game they deeply loved, supporting teams they deeply loved, and here there are others continuing to watch and enjoy the game in that very place. I think there something really important about that.

Dan Cruickshank:

It was characterised by all the years of denials by the various authorities and the sordidness of that, and the sadness of the action taking place to get to this resolution. It is not unusual for buildings to survive: the building itself was not at fault. We often live with building that have been host to disasters and buildings go on, that's ok. It is just such a sadly depressing tale of the incompetence and cover ups; the truth has come out in the end but there were many attempts to hide that truth.

Emily Gee:

It shows the power of place: sometimes our memory of something is so ghastly that it's steeped within the walls and the only thing to do is to take it away and create something else. It is useful to think what is happening with the Grenfell Tower site now: the decision to create a community-led memorial on that site is a really powerful thing.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

Hillsborough is a symbol than just the tragedy, it is a symbol of the fight for justice since and speaks to how we engage with power and authority and all of that legacy.

Emily Gee:

In a way it signifies the power of a collective people's voice in challenging and checking institutions, like we spoke about the previous site in Sheffield, and the idea of holding public bodies accountable and reminding of the power of the people to keep reinforcing the importance of that message.

Dan Cruickshank:

But what an arrogant attempt by the press at the time to manipulate what happened to make it the responsibility of the fans: it was so serious, all of that story.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

It reminds us that there are ongoing and unresolved cases for families even 29 years after the event.

Well, that's where we finish the Loss & Destruction category for A History of England in 100 Places. Before we go, we asked Mary Beard if she thought there was anywhere in England that deserved a special mention in this category. For this she picked the Lady Chapel at Ely Cathedral in Cambridgeshire.

She describes what remains of this medieval chapel as a wonderful aesthetic space in its own right. You can visit 100 foot long gothic chapel and see hints of the statues, sculptures and beautiful reliefs that would have adorned this chapel before they were removed and defaced after the Reformation: a poignant spot to consider art, architecture and faith in the face of change.

Mary also noted how destruction of this kind can leave us with a monumental space such as this that still has great significance today. So, on that note let's recap the ten Loss & Destruction locations which were: Must Farm, Bronze Age settlement in Peterborough; Whitby Abbey in Yorkshire; Greyfriars Monastery in Suffolk; The Mary Rose in Portsmouth; The monument in London; the Crystal Palace in south London; The Euston Arch in London; The wreck of the SS Mendi in the English Channel; The Farfield Inn in Sheffield and finally, Hillsborough Football Stadium in Sheffield.

Thank you for joining us as we explore England's past and present through the places we have lost and sometimes sought to recover. It has been an interesting but very emotive category. Next time we will be exploring a brand new category as we hear of Reverend David Ison's selections from your nominations in our Faith & Belief category. David will be revealing all but perhaps you can guess which ones have made his top ten? Get in touch and tell us at #100places and whilst you're at it, please leave a review on iTunes.

Thanks to my guests, historian Dan Cruickshank and Historic England's Emily Gee. I'm Suzannah Lipscomb and I hope you will join me next time.

Voiceover:

This is a Historic England podcast sponsored by Ecclesiastical Insurance Group. When it feels irreplaceable, trust Ecclesiastical.