Commemorating 100 Years of the Sinking of SS Mendi

To commemorate the centenary of the loss of the British ship the SS Mendi Historic England is publishing a new book, We Die Like Brothers.

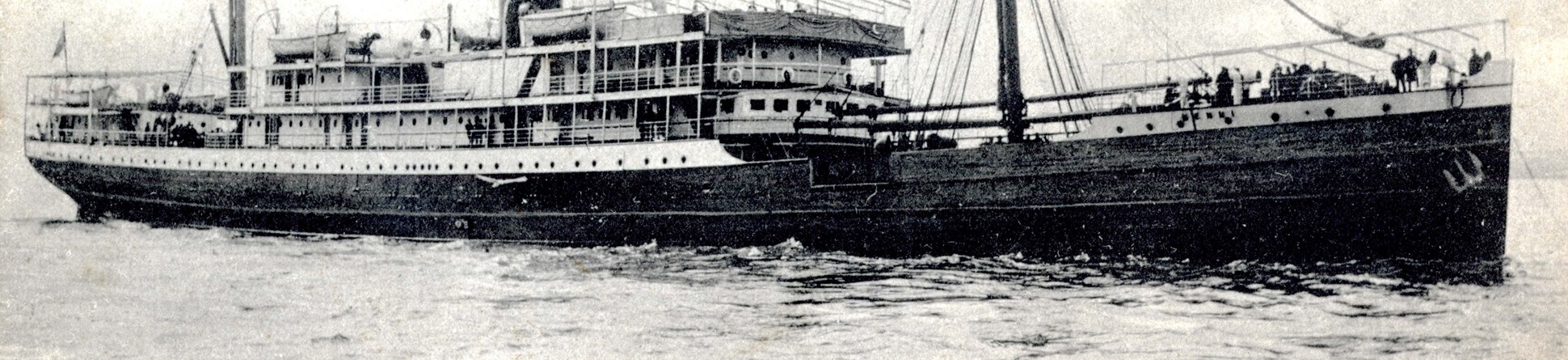

On 21 February 1917, the British ship, the SS Mendi was sunk off the Isle of Wight. It was hit not by a German torpedo, but by another British ship, the Darro, in thick fog.

On board were nearly 900 men, mostly black South African men of the South African Native Labour Corps (SANLC). They were on their way to support the war efforts on the Western Front. Many had never even seen the sea before.

After the collision, the Mendi didn’t stand a chance. Water flooded into the hold where many men were sleeping. Only two life boats were successfully launched and the Mendi sank in just 20 minutes. With no choice but to jump into the freezing cold water, over 600 men died.

The Darro made no attempt to rescue the men in the water, and the Mendi’s Royal Navy escort ship was able to find only a very few.

It was one of the First World War’s worst maritime disasters off the English coast.

Telling the story of the Mendi

We Die Like Brothers is the first book to tell the story of the Mendi, from both a historical and archaeological perspective, of the men who died in the wreck, and the political aftermath of the tragedy.

Written by experienced divers and archaeologists John Gribble and Graham Scott, We Die Like Brothers recounts how back in South Africa the families of the dead men were offered a mere £50 in compensation and few widows received pensions. The South African Government refused to award a War Service Medal to the men of the SANLC – and refused to allow them to receive British medals.

In war-weary Britain, the loss of the ship was soon forgotten. For decades, the wreck of the Mendi lay hidden. In 1974 recreational divers discovered it, and in 2006 Historic England began to study the wreck in detail and to encourage its archaeological investigation.

The remains of the Mendi are now recognised as one of England’s most important First World War heritage sites and is listed under the Protection of Military Remains Act.

Global conflict

The Mendi is part of a much bigger story. The First World War was not just a European war; it was a truly global conflict, and had repercussions worldwide.

Black South Africans weren’t allowed to fight by the new white-dominated nation of South Africa, but were employed in support roles. Many men volunteered for the SANLC, hoping it would help the political cause of the black majority population after the war. These hopes proved unfounded, and the Mendi became a focus of black resistance both before and during the Apartheid era in South Africa.

In 2003 South Africa’s civilian order for bravery was renamed the Order of Mendi, in honour of the shipwrecked men, and 2017 will see a series of commemorative events around the centenary of the sinking in the UK and South Africa.

We Die Like Brothers follows an exhibition of the same name funded by Historic England last summer at the Museum to the South African Forces at Delville Wood, Somme in France. Delville Wood is also the location of the principal South African memorial to their war dead.