First World War: Wartime Architecture

Throughout the 20th century, defence establishments have been important creators of new places, with housing often the most visible reminder of past industrial activities.

The creation of new munitions factories, in often remote locations, resulted in the displacement of tens of thousands of people all of whom needed housing. At 22 locations across England the Ministry of Munitions constructed 6,624 permanent houses, along with many temporary cottages and hostels. Elsewhere, at virtually all other munitions factories accommodation for key workers, such as the police and foremen, will be found. Many of these estates for munitions workers show the influence of pre-war garden city ideals, but in contrast to other public housing schemes, within these wartime estates the factory hierarchy is reflected through their architecture, in the allocation of detached or semi-detached houses, or more subtle differences such as the provision of bay windows.

One innovation introduced during the war was the widespread adoption of standardised prefabricated buildings. In August 1914, Major Armstrong, Royal Engineers, and his team devised a series of standard huts for new army camps that remained in use for the duration of the war. The huts were simple to manufacture and could be erected by unskilled labour, yet were flexible to be adapted to changing uses. In 1916, another Royal Engineers’ officer invented the quintessential military building of the 20th century, the Nissen hut, although none appear to have been built in England. The Royal Flying Corps also adopted standardised building types with distinctive hangars using curved Belfast truss roofs that could be fabricated by unskilled labour using inexpensive lengths of timber.

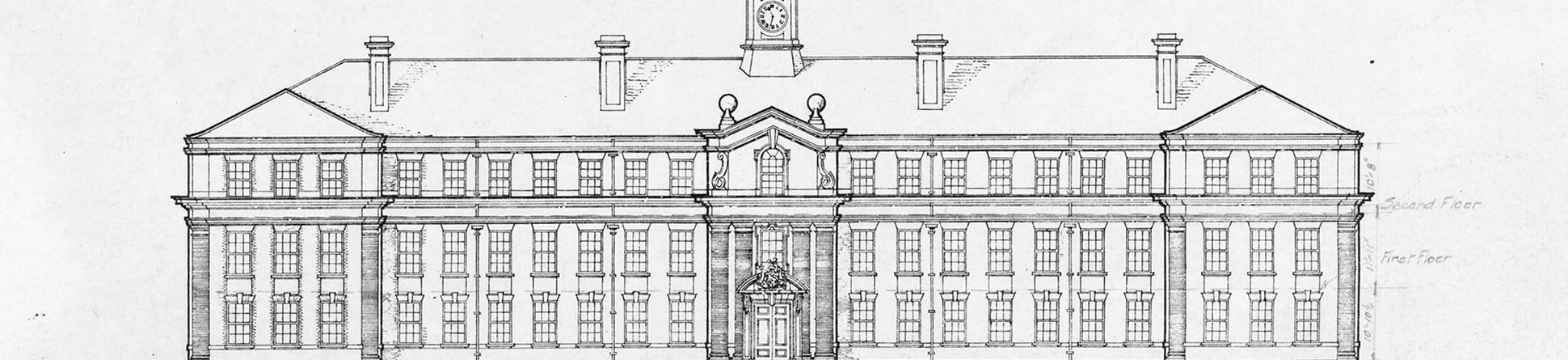

While many wartime factories were hastily erected using timber, corrugated iron and asbestos sheets many also maintained pre-war architectural standards. Most commonly the main administrative buildings were finished in neo-Georgian style with more functional production buildings to the rear.

Pubs for munitions workers

Historic England is setting out to discover what tangible remains of the so-called Carlisle Experiment, where Carlisle's pubs were nationalised during the First World War, can still be seen today. Also to be explored will be the wartime backdrop to the Experiment and assessment of its importance for the later development of English pub architecture.

In an attempt to reduce drunkenness amongst munitions workers, strict controls were placed on licensed premises. ‘Treating’, or buying rounds, was banned. It was even illegal for a man to buy his wife a drink.

In one of the first experiments, Carlisle's pubs were nationalized. Existing pubs were ‘improved’ by ripping out internal partitions to create larger rooms with dining tables. Interiors were painted an uninviting battleship grey. The aim was to provide good cheap food and discourage drinking. Many new pubs were also designed from scratch. The idea quickly spread beyond Carlisle.

Wartime Architecture

Please click on the gallery images to enlarge.

-

First World War: Land

One of the features of industrialised, mechanised, 20th-century warfare was its hunger for land.

-

First World War: Sea

At the outbreak of the First World War Great Britain was the world’s greatest naval power.

-

First World War: Air

Historic England has identified the most significant airfields and airfield buildings of the First World War.