Disability, Rehabilitation and Work

This section explains how work became a key element of the rehabilitation process for people with disabilities after the Second World War. As well as promoting their recovery, being able to work meant that they would be less dependent on the state.

In this section

Audio version: 🔊 Listen to this page and others in 'Disability Since 1945' as an MP3

- Overview: Disability Since 1945

- Back to the Community - Disability Equality, Rights and Inclusion

- Disability, Rehabilitation and Work (current page)

- Nowhere out of Bounds - Disability Access and Adaptation

- Disability and Sport: The Birth of the Paralympics - from Rehabilitation to World Class Performance

Treatment during the Second World War

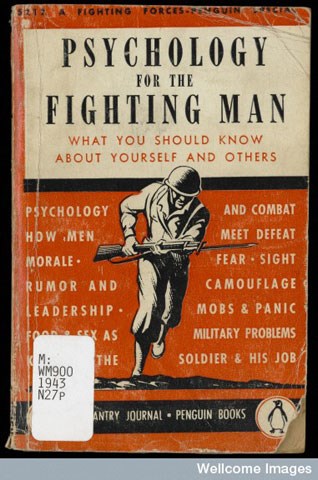

The treatment of seriously injured, burned and disabled soldiers and civilians during the Second World War centred on returning them to the war effort. If that was not possible, it might at least reduce their dependence on state or voluntary assistance for the rest of their lives.

Importantly, this meant that disability was no longer seen as an obstacle to employment, at any level. The most famous example of this was the acceptance of Douglas Bader (1910-1982) as an RAF pilot, despite his having lost both legs in a flying accident in 1931.

Fitness, mobility and purposeful activity

This new approach led to new ideas in the field of rehabilitation. Medical and surgical interventions came to be seen as just the first part of a longer process aimed at restoring fitness, mobility and daily living skills and combating depression through purposeful activity, including work.

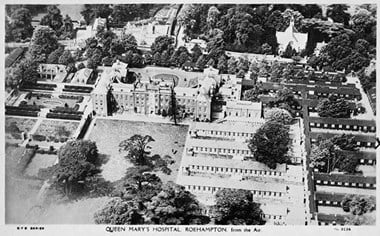

The physiotherapy profession grew enormously. There were significant advances in the design and manufacture of artificial and prosthetic limbs, particularly at Roehampton Hospital in south London.

Rehabilitation for all

By 1945, a network of convalescent and rehabilitation centres for disabled ex-servicemen and women had grown up around the country. Gradually, the new theories of rehabilitation were applied to the civilian disabled population.

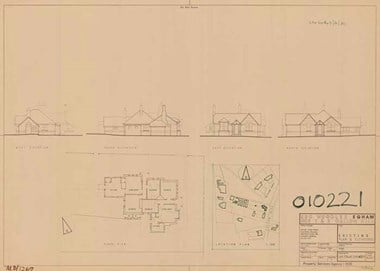

In 1946 the Egham Industrial Rehabilitation Centre in Surrey opened to civilians. It offered 'vocational guidance and purposeful training', particularly in building work, shoe repair and retail distribution. Roffey Park in Sussex specialised in supporting workers with mental health issues. St Dunstan's in Regent's Park, London continued to work with blind ex-servicemen, as did the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) with the rest of the blind population.

The National Health Service (NHS)

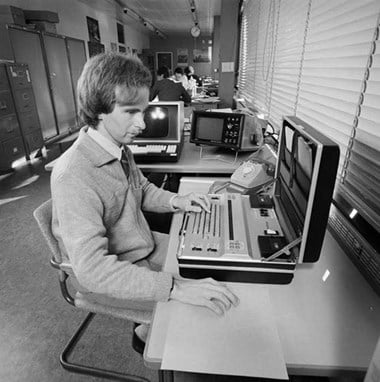

The NHS, created in 1948, had taken over most rehabilitation services by 1951. Amongst these was the Miners' Rehabilitation Service, which included centres at Berry Hill Hall near Mansfield and the Hermitage in Chester le Street, Durham. In the 1960s the Daily Living Research Unit at Mary Marlborough Lodge, based at the Nuffield Orthopaedic Hospital in Oxford, pioneered new rehabilitative techniques in daily living skills and new designs in wheelchairs and appliances.

Sheltered work settings

Work was seen as crucial both for rehabilitation purposes and to reduce dependence on the state in an era of labour shortages.

Following the Disabled Persons Employment Act of 1944, a network of factories was established, initially known as 'British Factories' and later renamed Remploy. The first factory was set up in Salford, Greater Manchester in 1946. By 1953 there were 90 factories employing 6,000 disabled people. Products included woodwork, leatherwork, mats and brushes; in Bristol and Halifax stump socks were manufactured for amputees. Veterans also worked in the Thermega electric blanket factory in Ashtead, Surrey.

Employment Registration Scheme

Outside these sheltered work settings, the government set up a registration scheme that required employers to take on a certain percentage of disabled workers. Occupations such as lift operator and car park attendant were reserved for disabled people.

Inclusion in mainstream employment

Later in the century, doubts arose about the effectiveness of sheltered work. There was now a drive towards bringing disabled people into mainstream employment, in line with the idea of their full participation in mainstream life.

High profile disabled people such as politician David Blunkett, scientist Stephen Hawking and athlete Tanni Grey-Thompson have reached the top of their professions. Yet unemployment amongst people with disabilities remains a serious issue.

Watch the BSL video on disability, rehabilitation and work

Disability, Rehabilitation and Work

Please click on the gallery images to enlarge.