Case Study: Edward Long Memorial, St Mary’s Church, Slindon, West Sussex

St. Mary’s Church houses a memorial to Edward Long (1734-1813), former colonial Governor of Jamaica and vocal defender of the slave trade. To reinterpret the memorial, a simple and low-cost document has been hung beneath the structure at eye-level. The document shows contextual wording developed by historian Professor Catherine Hall, University College London, in collaboration with the local Parochial Church Council (PCC).

Overview

- Site and type of structure: Wall memorial, inside St. Mary’s Church

- Location: Slindon, West Sussex

- Country: England

- Legal protection: The church is a Grade I listed building

Introduction

Edward Long (1734-1813) is buried at St Mary’s Church in the village of Slindon, West Sussex. While few people outside academic circles are aware of Long’s history, he was a staunch defender of slavery. A slaveowner and a colonial Governor of Jamaica, Long’s polemical book 'The History of Jamaica' was a seminal text for pro-slavery politicians in the late 18th century, depicting African and Jamaican residents on the island using virulently racist language.

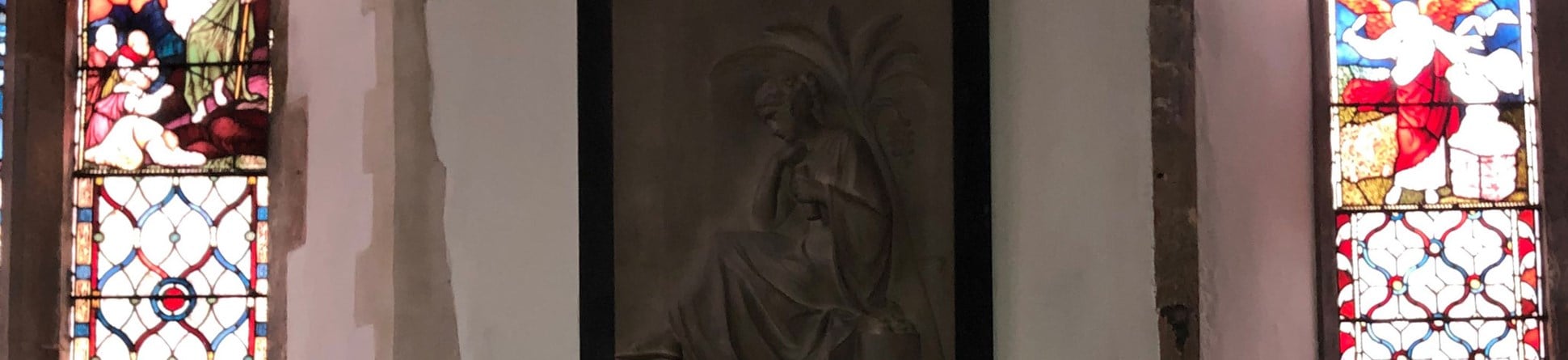

Long is buried beneath the altar of the church and commemorated by a substantial memorial, cast in white marble and fixed in a prominent position in the chancel. The Neo-Classical monument, installed shortly after Long’s death in 1813, was designed and executed by celebrated sculptor Richard Westmacott. It is therefore of artistic as well as historical significance and forms part of the Grade I listing of the building.

The context for reinterpretation

While few residents in Slindon initially had knowledge of Long or his history, his monument received national publicity in 2015 after his links with the slave trade were explored in a BBC documentary 'Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners'. Television crews visited St Mary’s Church for the documentary and filmed Long’s memorial.

Following the BBC series, the PCC met to discuss the memorial and determine an appropriate way of acknowledging Long’s involvement in the history of slavery. Initial meetings within the PCC were reported to have been inconclusive and any response was put on hold. However, this was revisited in response to the racial justice protests in 2020 and the toppling of the Edward Colston statue in Bristol, which raised concerns among members of the PCC about the possibility of vandalism. At the time, the Long memorial had also reached a new audience through a repeat of the BBC documentary series on slavery.

Assessment of options

The PCC decided that relocation would be impractical and costly. The memorial was fixed in a prominent position next to the right of the high altar and relocation would have required substantial repair work to the chancel. The structure is also situated in a Grade I listed church and therefore subject to the equivalent of listed building consent. Such a major change would require consent through the Church of England’s Faculty Jurisdiction process as the building and fixed contents are protected by national legislation. Moreover, despite the BBC documentary, no local or external voices had suggested relocation of Long’s memorial.

The memorial was also of artistic and historic interest as outlined above.

Consequently, the PCC felt that a reinterpretation document placing the memorial in context would provide a simple yet powerful means to recognise and address Long’s controversial history.

What was done and who was involved?

To seek advice on the contextual wording for the reinterpretation document, the local Church Warden approached the presenters of the BBC series, who introduced him to Professor Catherine Hall – an historian, author of a book on Edward Long and Chair of the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership. Professor Hall drafted a short document explaining Long’s views on slavery, which was put to the PCC for approval.

Hall’s contextual wording was welcomed by the PCC members and accepted with two provisos: that a statement was added to express the PCC’s repugnance for Long’s views and associations, and that the document would also outline the current position of the Church of England regarding its links to the slave trade.

The agreed wording was printed in bold on a simple A4 sheet and is mounted, at eye-level, in a frame below the memorial. Since the project did not involve any physical works, there was no need for the parish to consult planners or the local Diocesan Advisory Committee (DAC) of Chichester.

Public response

Few people in the village of Slindon were familiar with Edward Long or his involvement in the history of the slave trade prior to discussions about potential reinterpretation, and the Church had never received any complaints regarding the memorial. The building welcomes visitors but does not record numbers, beyond inviting them to sign a visitors’ book. To date visitors have not left any comments, either positive or negative, that refer to the reinterpretation. The parish now feels that they have responded to Long’s problematic legacy effectively.

Reinterpretation text wording

"Edward Long (1734-1813), memorialised by his family here in this church was the author of the three volume 'History of Jamaica' published in 1774 and still in print today. Born in England, he came from a family of slave-owners who had property in Jamaica, both in land and people, over generations. he lived there for 11 years, actively managing Lucky Valley, the sugar plantation he owned which depended on the enslaved labour of 300 men women and children. In 1768 he returned to England and became active in the struggle against the abolition of the slave trade. The 'History' strongly defended slavery as necessary institution in a plantation economy and one which contributed much to British wealth and power. Long believed that Black people were essentially different to White people and that they were born to serve. His ideas about racial difference were influential both in the UK and the US. They were challenged by abolitionists at the time and have been ever since by anti-racists.

While recognising the leading role that clergy and active members of the Church of England played in securing the abolition of slavery, it is a source of shame that others within the Church actively perpetrated slavery and profited from it. In 2006 the General Synod of the Church of England issued an apology, acknowledging the part the Church itself played in cases of historic slavery.

The Church today is committed to support every effort to oppose human trafficking and all other manifestations of slavery across the world. This parish abhors the views of Edward Long and all others who espouse racism in any form."

Lessons and insights

The case at St Mary’s exemplifies how simple strategies to reinterpret heritage can support thought-provoking reinterpretation of sites or assets that have become contested. This approach – of adding concise contextual wording beneath the memorial, without undertaking physical changes to the building – is one that could easily be replicated.

This may be particularly appropriate for places of worship and other sites with limited financial and staff resources, or those looking to respond promptly to challenging histories while exploring longer term solutions.

While the process was relatively simple, stakeholders on the project stressed the importance of collaborating with those who had detailed knowledge of the history involved when drafting reinterpretation materials. The PCC at St Mary’s felt fortunate to be supported in this work by Professor Hall, a distinguished academic who had undertaken extensive research on Edward Long. Hall offered a clear and candid contextualisation of Long’s views based on her work. The PCC’s response was to accept Hall’s account of Long’s life and views in full.

Involve people who really know about the person or institution so that there can be a clear defence of whatever the new wording might be.

For other places of worship in similar scenarios, simple contextualisation documents may form a straight-forward means to articulate why a heritage asset might spark controversy. Such notices can reveal aspects of history which have been forgotten, not told or concealed and contribute to the creation of an inclusive understanding of our past.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the case in Slindon was motivated by very specific circumstances: since being featured in the BBC documentary led to action to reinterpret the memorial that may not otherwise have taken place. The programme provided the Parish with a detailed account of the notoriety of Long’s views, and a route to the historical expertise which could contextualise his life. It is unclear whether the protests in Bristol and elsewhere could also have led to this response without the documentary, although they certainly reignited interest in the need for reinterpretation. Other parishes may need more guidance on approaches and sources, to decide whether to reinterpret similar heritage assets proactively.

Key lessons:

- Simple and easy-to-understand notices or signs can provide effective interpretation and may provide a good way of responding to contested, or potentially contested, monuments (or other types of heritage asset). They are also an honest means of the current owners or, in the case of churches, congregations, setting out their own rejection of enslavement in the past and the present.

- Even simple responses require expertise and consultation.

- In some cases, notices or signs may provide a useful interim response while more complex responses are prepared – potentially involving wider consultation and the consideration of other artistic responses (see other case studies).

- By keeping the original monument and reinterpreting it, new layers of meaning can be added which help to ensure lessons from history are not lost. Particularly with subjects that are less well known, this provides an opportunity for conversation and learning that otherwise may not have been available.