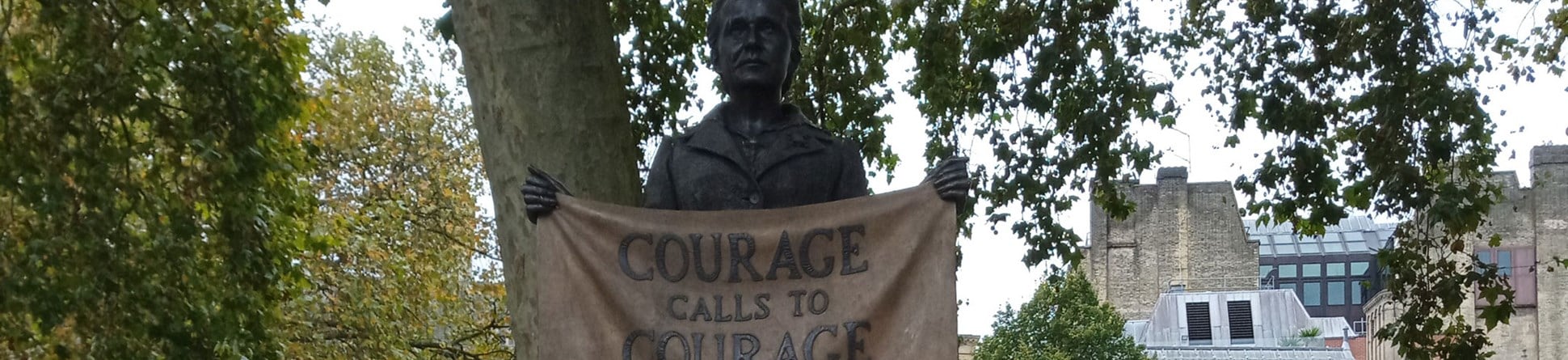

Case Study: Millicent Fawcett Statue – Parliament Square, London

Following a campaign and petition noting that all 11 statues in Parliament Square were of men, a statue of Millicent Fawcett was erected to coincide with the centenary of some women being granted the right to vote in 1918. [See footnote 1]. The principle of the statue’s creation secured a broad coalition of political and civic support. Alongside Fawcett, the names and portraits of 59 women and men who campaigned for women’s suffrage are inscribed on the plinth.

Overview

- Site and type of structure: Bronze statue of Millicent Fawcett

- Location: Parliament Square, City of Westminster, London

- Country: England

- Legal protection: New, not listed, within the Grade II registered Parliament Square and next to the Westminster World Heritage Site

Introduction

Parliament Square in the City of Westminster is a focal point for national politics, for civic protest and tourism, given its symbolic location across from the Houses of Parliament. The square now contains 12 statues of historical political figures. Statues of George Canning, Robert Peel, Edward Smith-Stanley, Benjamin Disraeli and Viscount Henry John Palmerston were erected in the 19th century and were later joined by statues of Abraham Lincoln (1920), Jan Smuts (1956) and Winston Churchill (1973), with David Lloyd George (2007), Nelson Mandela (2007) and Mahatma Gandhi (2015) added in this century. Millicent Fawcett (2018) is the first to depict a woman and the first to be designed by a woman.

Context for reinterpretation

In March 2016, on International Women’s Day, feminist writer and campaigner Caroline Criado Perez began a public campaign to install a statue of a woman in Parliament Square, in time for the centenary of the Representation of the People’s Act in 2018. The campaign secured the support of Sadiq Khan, newly elected as Mayor of London in 2016 and Theresa May, who became the UK’s second female Prime Minister that year’. An online petition gathered 74,000 public signatures and wide support across the political spectrum.

The 2018 anniversary of some women first securing the right to vote was a focal point for that campaign, and was also being marked by a wider range of educational and cultural activities. The centenary commemorations of the First World War included a cultural programme, 14-18 NOW. This explored the social impacts of the war, including women’s suffrage.

Assessment of options

The core principle of the campaign was widely accepted, given the 11 statues of men in Parliament Square. However, it took time to reach an agreed outcome; there were long discussions about who should be portrayed, a suffragette, a suffragist, or 'everywoman'. Competing campaigns over whom to recognise led to proposals for statues of Millicent Fawcett and Emmeline Pankhurst both being considered at the same planning meeting at Westminster Council in early 2017.

In April that year, the Greater London Authority confirmed their decision to commission the Fawcett statue. Planning permission to install the monument was then granted in September.

What was done and who was involved?

The breadth of the civic and political coalition for the Fawcett statue was decisive, including from Members of Parliament across parties, Mayor of London Sadiq Khan and the Greater London Authority (GLA). The GLA in particular was able to assist with the navigation of planning policies for the statue, and to utilise its influence in the arts and culture sector to convene an advisory panel for the commission of the sculptor.

Only female artists were invited to seek the commission and Gillian Wearing was chosen.

There were some objections from male sculptors to this, with some arguing that the quality of the proposal should be the determining factor. The Mayor’s office were firm that the centenary of women’s suffrage made it appropriate for both the subject and the artist to be women. This was not a theme of wide public discussion.

The need to raise funds for the statue was overtaken by the support of the 14-18 NOW centenary cultural programme, with a grant of £850,000.

Historical advisers worked with the artist on the proposal to recognise other campaigners around the statue. 59 other figures were chosen. Including both suffragettes and suffragists was seen as crucial to the legitimacy and breadth of support. There were also efforts to ensure diverse representation through the inclusion of two women from ethnic minorities and women from the LGBTQ+ community, involved in campaigning for women’s suffrage. There was little controversy about the figures chosen, though some had engaged in direct action and violence. One or two potential candidates were excluded, where activities after 1918 could generate controversy, such as a campaigner who later became prominent in the British Union of Fascists.

Historic England warmly welcomed the statue and advised that equivalency of scale, quality, form, and materials was important in this particular context and commented in its advice letter (dated 25 July 2017) that “The first statue of a woman in Parliament Square presents an important opportunity and the subject and design of this proposal, designed by Gillian Wearing, embraces this with an elegant solution. In summary, we warmly welcome the statue which would make its own historical and artistic contribution to this important commemorative landscape.”

Public response

Almost 85,000 people signed the initial petition to install a statue of a woman in Parliament Square. There was very broad civic and political support, symbolised by the Conservative Prime Minister and Labour Mayor unveiling the statue together. Objections to the principle of a campaigner for women’s votes being commemorated in this way were marginal – comprising angry emails to the Mayor and online social media comments – and were not covered in, for example, major conservative media outlets. There was much more debate within feminist and broader civic circles about the particular merits of Fawcett: on themes including what forms of feminism were celebrated today, how and why.

Qualitatively, the statue has become popular as a focal point for civic campaigners and for tourists, with more public engagement and response than most of the older statues. There has been no formal research into public attitudes or responses to the statue, since its unveiling.

Lessons and insights

Anniversaries catalyse. The pace of development of the project reflects this. Inclusive history can often command a broad consensus, where proposals to remove statues may polarise opinion sharply. Parliament Square exemplifies an implicit test of when inclusive history commands the breadth of consensus: those recognised need to be perceived to have the historical status to be relevant peers of the other statues in this setting. Few, if any, have claimed that Mandela, Gandhi and Fawcett do not meet this test.

The Fawcett case exemplifies how some forms of ‘contestation’ can be actively pursued as positive and educational. Arguments about whom to recognise, why and how can provide opportunities for experts, academics and civic voices to engage in broader public debate. In turn this can widen and deepen our knowledge about how the role of suffragists and suffragettes was contested at the time and help us to explore how we understand historic politics and protest today. A pluralist approach to this statue itself (recognising 59 campaigners) and the existence of several other projects, particularly due to the anniversary, mitigated arguments about ‘which woman’ merited the honour. Many women could be recognised here, as well as with new statues in Leicester, Manchester, Oldham and elsewhere.

Experts and academics were delighted to participate in a historic moment for commemoration, but felt that they were not equipped with advice or support to engage with public responses, from intensely engaged public arguments within feminist circles, to a small minority who engaged in trolling and abuse from the misogynistic margins. Increasing the pluralism of representation in Parliament Square appears likely to have helped to broaden the legitimacy of the existing statues. This was not the purpose of adding the Fawcett statue, but a probable by-product is that it will contribute to defusing or mitigating future arguments.

It should also be noted that, while this is one prominent statue, research indicates that the stock of public statues in London remains predominantly male, with more animal statues than named women. Future commissioning strategies need to continue to be aware of and seek to redress this disparity.

Key lessons:

- Anniversaries of historical events can help catalyse funding and public support for reinterpretation initiatives

- Recognising multiple figures can mitigate contestation over who is represented in inclusive heritage projects

- When considering an intervention into a historic landscape with existing monuments, a contextual point about equivalency of scale and prominence should be carefully considered

- Experts who are publicly involved in work on reinterpretation and contested history should be equipped with appropriate resources and after-care, to help prepare them for public responses or possible criticism

Footnotes

- In 1918, suffrage was extended to women aged over 30 years old who met a number of property qualifications. The Equal Franchise Act of 1928 later extended voting rights to all women over 21.↩