100 Places Podcast

Join us as we travel across England visiting well-known wonders and some lesser-known places on your doorstep - all of which have helped make this country what it is today.

This is a transcript of episode 1 of our podcast series A History of England in 100 Places. Join Emma Barnett and category judge Professor Lord Robert Winston as we begin our journey through the history of science and discovery in England.

A History of England in 100 Places is sponsored by Ecclesiastical

Voiceover:

This is a Historic England podcast, sponsored by Ecclesiastical Insurance Group.

Emma Barnett:

Welcome to Irreplaceable: A History of England in 100 Places, I’m Emma Barnett and in this series we’ll be exploring the amazing places that have helped make England the country it is today. We have been asking you for places you think should be on the list and we’re happy to say we’ve received hundreds of nominations from people across the country. You can still nominate at 100 Places. Together we’ll find out just why our panel of expert judges, including Professor Robert Winston, George Clarke and Mary Beard selected these hundred locations from your nominations to tell the story of England.

You’ve nominated so many extraordinary sites and our Science & Discovery category judge Professor Lord Robert Winston has chosen ten places which he thinks best demonstrate the importance of science and invention to the identity of England. We’ll be hearing from him about some of his choices.

Professor Lord Robert Winston:

We think of Britain as being coal mining and steelmaking but actually chemistry and the technology that comes out of chemistry was a very big reason that Britain became prominent and world class.

Emma Barnett:

Professor Winston is a professor of science and society and Emeritus Professor of Fertility Studies at Imperial College London and I really look forward to hearing his choices. Today I’m joined in the studio by Jane Sidell, an Inspector of Ancient Monuments at Historic England who has a real passion for science. Jane, welcome. First of all tell me what does that title mean? I’d like to know a bit more.

Jane Sidell:

I’m afraid it means I have the best job in the world! As an inspector of ancient monuments I look after some of the most important archaeology in London and that includes sites like Hampton Court Palace all the way down to a tiny scrap of the Roman Forum that is buried beneath a hairdressers in Leadenhall Market. It is my job to make sure the sites are protected and preserved but also we show them off as much as we can to anyone who wants to know about them.

Emma Barnett:

Wow! In this episode we’re going to unveil the first six irreplaceable science and discovery locations. So let’s begin with nothing less than our modern measurement of time. Doctor Louise Devoy is curator of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich and she gave us a tour.

Dr Louise Devoy:

If you had come here a few hundred years ago this would have just been a hunting lodge in the middle of a royal park. Then in the 1670s it was realised that people needed to do a lot more astronomy to try and create accurate star charts that could help navigation at sea. It was becoming more important for trade and travel across the globe. So the observatory was set up in 1675 and it was up to the first Astronomer Royal - John Flamsteed - to very diligently map the stars as they moved across the sky from east to west, timing the exact moment at which they moved across the meridian, the north-south line.

Today we’re a visitor attraction and we welcome over 700,000 visitors a year, for the great view across the park and across East London. We’ve got lots of different historic parts to see but we’ve aslo got our contemporary astronomy to see. You can learn about techniques that astronomers are using to probe the universe. You can also see photographs taken by amateur astronomers across the world.

We are standing on the historic prime meridian, so you can have one foot in the eastern hemisphere and one foot in the western hemisphere. It denotes 0 degrees longitude and it’s a really good way of telling how far east or west you are. If you look on a map you’ll notice that there’s a line running through Greenwich that denotes 0 degrees longitude, known as the prime meridian. That line really has saved thousands of lives across the centuries; it has been used for navigation and timekeeping and we’re still very much reliant on mapping and systems that are based upon the Greenwich system.

Behind me we have the Meridian Observatory and that is where the astronomers would set up their telescopes and clocks. They would open up the hatch in the roof and watch the stars as they appeared to move across the sky and then as the star crosses the meridian they would check the clock and use time as a measure of position.

I’ve been a curator here at the observatory for about three and a half years now. I think the Royal Observatory is simply irreplaceable within England’s history because it just means so much to so many people. Originally it was very much about navigation for people at sea and about safety and trade but now it’s such a part of our lives, whether it’s looking at our watches and using Greenwich Mean Time or looking at a map or GPS coordinates. All of those technologies and ideas stem from work that was originally done here. It’s global history.

Emma Barnett:

Well, it means a lot of things to a lot of different people. Jane, you are particularly passionate about this location, aren’t you?

Jane Sidell:

The Royal Observatory is a stunning site on so many different levels. Its role in science is astronomical, if I can use that pun, but it’s also absolutely stunning. It’s important not just for the science that has gone on there but it’s important in the history of science. This is one of the birthplaces of the enlightenment movement, it’s where we went from a somewhat archaic nation to a completely modern, scientific, forward looking nation. It’s associated with astonishing people like Christopher Wren and the birth of the Royal Society; it has so much science seeping out of its walls and so much history seeping out of its walls. I love it to bits!

Emma Barnett:

You’re not alone in that. I’ve been, it’s absolutely beautiful and people do feel very passionately about it. It is no surprise that London’s clock-makers became known for their high standards with something like that.

Jane Sidell:

They had to. This was where the competition to actually make these chronometers that would save the lives sailors happened. They had to be of such a standard that they could go to sea and survive everything that would be thrown at them.

Emma Barnett:

Trade and industry seem to have played a role in shaping the Royal Observatory. What do we know about that?

Jane Sidell:

This is because of the sheer amount of wealth and money that was coming into Britain and going out of Britain, exported around the world and quite frankly the amount of money needed to sustain the development of astronomy, the research into timekeeping and the research into understanding how the world works.

Emma Barnett:

Well, we’ll be exploring some key trade and industry locations in later episodes of this series. Do not miss that. And now to our second location, which is the Brown Firth Research Laboratory in Sheffield. This is one I have to admit I hadn’t heard of but others will have done because it is better known as the birthplace of stainless steel in 1913. Stainless steel is the world’s best known and most widely used steel alloy and the laboratory in which this discovery was made still stands today. Today it is branded with the English Pewter Company outside it in big mark letters with a memorial plaque to a man named Harry Brearley. His goal was to make a high melting point steel for use in gun barrels by incorporating chromium into the metal, thus by accident - often the best way - rustless steel was born. Now Jane, for you and others that might not know very much about this site and that stainless steel was made there, what does it mean to you?

Jane Sidell:

It’s used all around the world, by almost everyone, almost every day. It’s the movement from metals which are so vulnerable to weather, to corrosion and simply rusting, to a metal that is structurally sound and stable. We know Sheffield for making knives and forks but this is more about having the ability to make buildings that are going to stay up. So hugely important in the transformation at this point of how buildings work.

Emma Barnett:

But also in terms of Sheffield, it has this rich history of industrial heritage.

Jane Siddell:

It has, it’s absolutely beautiful because it’s not just the production of the metals, it’s not metal coming out as at end product, it’s everything that goes with it it’s the construction of beautiful buildings and beautiful canal-ways so that there are very large areas of Sheffield that fortunately we have not completely lost.

Emma Barnett:

Do you think that the spirit of Sheffield today reflects its past, do you think the people who live there are sort of proud of this history and know of it?

Jane Siddell:

I think that they are. My mother actually was born nearby and I used to be taken there as a treat when I was younger and it is a stunning place. People are very passionate and very keen that these buildings survive that that they are championed. Money has played a part. It is a town which has a strong working class history and tradition and so sometimes being able to just defy saving these buildings when other other things can be needed can be quite hard but there is a huge passion about Sheffield and about what puts it on the map and the loss of these buildings would be something that would not be tolerated.

Emma Barnett:

And this particular research laboratory is a red brick building built at 1 Blackmore Street for research. It is a kind of amazing place to be able to go to and to have isn’t it? To be able to go and see where this whole transformation occurred is hugely important. It is really exciting that this site has been nominated.

Emma Barnett:

Let’s stay on the topic of great engineering feats for our next location which is the Imperial Chemical Industries Laboratory. Of their many former premises we picked a little factory in Widnes in Cheshire.

Jane Siddell:

This is a fantastic area because it is such an interesting thing that happened. A chemist called Charles Suckling discovered halothane in the 1950s. This was a safer anaesthetic which particularly usefully was not flammable. It was used widely until the 1980s. The really important thing about this material is that Charles Suckling actually did clinical trials so this was a pioneering example of a clinical drugs trial.

ICI was Britain’s largest chemical manufacturer for part of the 20th century. They made polymers, fragrances, flavourings and even helped developed Dulux paint before the Second World War and they helped the government with a nuclear weapons program during World War 2. I also know this company had a pharmaceutical arm that helped develop antimalarial drugs, beta-blockers and even tamoxifen, the breast cancer drug.

Professor Lord Robert Winston:

Chemical industry is and has been extremely important to Britain’s economy for a very long time. We think of Britain has being coal mining and steel-making but actually chemistry and the technology which comes out of chemistry was a very big reason why Britain became prominent and world-class and it’s effected and still effects the way we teach in our universities.

ICI is particularly interesting because it is a front runner of chemical industries and its technology is quite remarkable and I think halothane is really a very important discovery. It’s one of the most important drugs that we have every produced. It goes up there with penicillin; it goes up there with ergometrine which has stopped people bleeding after childbirth. Halothane has given people peace calm sleep and pain relief during major operations.

Halothane’s remarkable compound is one of the first really artificial ones that have been made specifically as an anaesthetic and what intrigues me about halothane is that like all anaesthetics we still don’t really understand how they work - we don’t know the chemistry of the brain that they really interact with so that’s a mystery but whatever halothane turned out to be extraordinarily safe because of worldwide margins of over dosage which would not kill somebody but which might make them deeper. It also carries with it a pain relieving property after anaesthesia.

Emma Barnett:

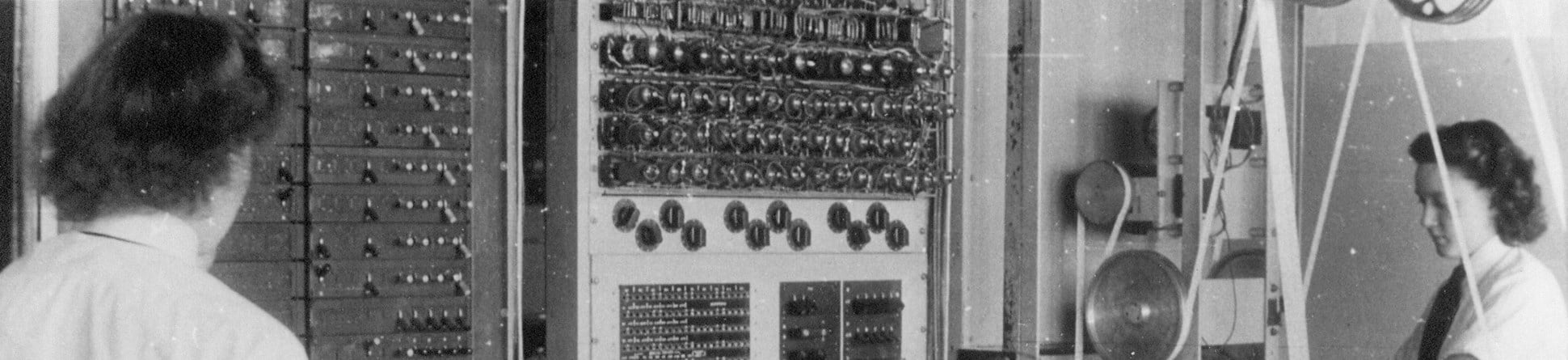

Thank you, Robert. Medicine was not the only area to benefit from great strides in science and discovery during war time. Our next location is no surprise. It receives around a quarter of a million visits each year as a museum but in 1938 MI6 acquired this Victorian mansion and country estate in Buckinghamshire for vital intelligence work and it was all about people not knowing it existed. Let’s hear from Dr David Kenyon, the Research Historian at the famous Bletchley Park.

Dr David Kenyon:

The first reason Bletchley Park is very important is because the work here helped win the second World War but its on-going relevance is that things were done here not only with code breaking but also with information management that remain absolutely relevant to this day.

Bletchley was very different and very new because not only were they using machines as part of the code breaking process but also the whole site was structured like a factory that that is the first time that’s really been applied to intelligence in war. What that allowed was huge number of messages to be broken. Enigma messages for example the famous German cipher machine was one of the typical targets of Bletchley Park. Enigma messages are typically very short and they don’t contain much information but if you break thousands of them every day then you can piece by piece build up a very detailed picture of what your enemy is doing and it’s that industrialisation of the process which was done for the first time here at Bletchley.

It was very easy to dig a short trench and install some cables and give the Park very high levels of electronic on activity both with London and with the rest of the UK. Wireless messages were being intercepted in what we call Wi Stations which were located all around the UK so even in 1939 what we now call bandwidth was very important. The con activity of the site electronically was a key consideration in its purchase.

Initially in 1939-40 they built a series of the famous wooden huts. People would have heard of Hut 3 and Hut 6 which were places where code breaking took place. They were replaced in 1942 and 1943 by very large concrete mostly single storey office buildings. We still have a small area of gardens and lake just outside my window here. The jobs were broken down into many many small stages so a lot of the people who worked here would have only done one of those little stages. Many of them didn’t even know what it was for. For every one sort of Alan Turing or Gordan Welchman who is a great genius in command of the whole picture you have several hundred junior people.

Computers as we know them today were first developed in the late 1940s and early 1950s. But there are certainly things happening at Bletchley that prefigure information technology as we know it. The first part of that is the creation of various decryption machines; the so called Bombe machines were the first ones which were electro-mechanical system that searched through many different possible enigma settings to find particular keys for enigma messages and then latterly Colossus was produced which was an electronic valves machine used in breaking German teleprinter messages but I think the computer analogy is better made about the whole site as it has all the components that we think of in a modern computer or information processor machine. Data comes in at one end, its processed, its stored, its manipulated and outputs are created that come out at the other end. The difference is that’s been done by thousands and thousands of people who have been programmed rather than electronic circuitry.

We are sitting here now in my office which happens to be a room which was little used but for breaking German labour codes during the war and I feel that history every time I come in here and I have been working here for two years! World changing events happened in these quite modest buildings.

Emma Barnett:

David Kenyon, the research historian at the famous Bletchley Park. It’s fascinating Jane that he thinks because it was structured like a factory and the way the operations were organised at Bletchley that that was a big part of how modern computing has evolved. Do you agree with that?

Jane Siddell:

I think that he has a very strong point there. I think he is quite right because the task that they were faced with were absolutely enormous and yet the people working there were undaunted. I think they had to industrialise the handling of data in order to have any hope at all of trying to achieve what they were doing.

Emma Barnett:

It’s interesting as well that when you look at the makeup of that workforce it was very unique for the time and the times that had gone ahead of it because the majority of the workforce were women - 75% of them.

Jane Siddell:

I think this is fantastic but of course there were so many women who really wanted to do something and, let’s face it, these are tasks for which you need a brain. Women are just as good at this - it’s simply intelligence.

Emma Barnett:

It’s fascinating to maybe even think just because of that very point it wasn’t manual labour it was about your brain - that perhaps it really did convince those who didn’t think women could do those sorts of things having these sorts of jobs for women at that time.

Jane Siddell:

Yes, because the results came from it. There was simple people getting on and doing these tasks - hugely difficult decryption tasks but then some of it was also as we heard about the data handling and about people being a small part in a very large, very well organised efficient process.

Emma Barnett:

Now there's one other thing that we have to mention about Bletchley Park and we are talking about science and we are talking about buildings and monuments but of course these places are all about the people. Bletchley Park is now indelibly associated with Alan Turing. I don’t know if this would have been part of his legacy that he would have wanted. I'm sure he would have wanted his legacy to be all about the maths, the decryption, the development of the computer systems but because of the stories associated now, Bletchley Park has to be associated with the way that, as a nation, we've treated gay men in the past and it was very much gay men and part of a shameful part of British history and something that fortunately I think we are now able to confront as a nation - the way that he was persecuted, prosecuted and chemically castrated.

Jane Siddell:

It was only earlier this year that the law was given royal assent to move this outdated offence from the records of people both living and deceased and I think it is important that with sites like this as well as the science and the triumphs and the interesting stories we acknowledge some of the ways that these people have been treated so I am really pleased that Bletchley Park has made it as one of our 100 places.

Emma Barnett:

We should say that Bletchley Park did stop operating in 1946 when GCHQ moved to London and the site was nearly redeveloped but the Trust took over it is of course open for you to visit today as so many do each year.

And now to our fifth location. It is another that we might easily take for granted. Have you heard of Ouse Washes March in Cambridgeshire. This is a huge water channel that was cut between the 1630s and the 1650s to drain the fenlands and make a temporary flood water storage area. King Charles the First granted a drainage charter to a group of investors who called themselves The Adventurers. This stretches 20 miles between Earith and Downham market and the biodiversity of these wash lands makes them an area of special scientific interest. Professor Robert Winston tells us why he thinks this place has shaped England’s story.

Professor Robert Winston:

It is a remarkable piece of the country, flat and cold in the winters and flooding is the thing that was faced and of course flooding and the loss of agricultural land and also livelihoods was all important. Ecologically and geographically the marshes are interesting because apart from being a rich source of wildlife which I have visited as a school boy it is an interesting engineering feat. I mean the engineering of low line of country something which has been challenging and is going to be more challenging with climate change and with sea waters rising.

Emma Barnett:

Our last irreplaceable science and discovery location for this episode sounds like a stately home but is far from it. Calder Hall was not just England’s but the world’s first commercial nuclear reactor. It is located in Cumbria just over a mile inland from the Irish Sea. Queen Elizabeth hit the on switch in a ceremony in 1956 and became an era of nuclear energy. That was a ceremonial switch by the way, I should say. The reactor was already supplying energy to the National Grid.

Jane Siddell:

It is probably worth mentioning that the public didn’t know and were really fed the line about cheap electricity but of course the reactors were used for something else as well. Until 1995 they were actually manufacturing weapons grade plutonium so we were making nuclear weapons here. Now of course plutonium is not made here anymore and Calder Hall was shut down in 2003 and decommissioning is still going on and employs hundreds of people in the area because of course these plants are enormous and have to be very very carefully decommissioned and it is part of the Sellafield Estate that most people are aware of has the windscale power station. Now really sadly there were 4 amazing cooling towers and I remember as a child actually seeing these cooling towers and just thinking it is part of an almost alien landscape because they are so enormous – the scale is huge but unfortunately it costs so much to maintain these that they had to be demolished. They were demolished in 2007 and of course people love enormous buildings being destroyed which in some ways is an enormous shame but it is awful that they had to go but simply the cost of them couldn’t be maintained.

Emma Barnett:

Professor Robert Winston explains why this made the list.

Professor Robert Winston:

Calder Hall is important because in the 1960s Britain led the world in nuclear fusion and nuclear fusion engineering and its use of nuclear power for peaceful purposes and Calder Hall was the first such plant to produce nuclear energy by nuclear fusion and perhaps it is rather important that we celebrate or make an icon of Calder Hall which is, if you like, historically so important as a change in the way we produce energy. Twenty per cent of our power that we now use on the National Grid roughly speaking is nuclear fusion and over the next few years that needs to increase if we are to have a balanced portfolio and is a big issue for Britain as it is a pretty big issue for a lot of countries that don’t have resources to many other renewable energy sources. I suppose also Calder Hall is interesting because of course the whole of the country in that area has been advanced because it is a major source of employment. I think it is absolutely right that Calder Hall should be elevated to this significance in our 100 places in England because without that extraordinary history of nuclear engineering I think now Britain would be in a very serious disadvantage. We would have to be buying up at great expense far more than it would cost if we did it ourselves from other countries - our inter-connectors from Scandinavia, France, Iceland and so on.

Emma Barnett:

And that’s all we have time for in this episode but, have no fear, we still have four irreplaceable places to explore in our Science & Discovery programmes. We’ll be hearing about the places behind innovations in health and disease, right through to our exploration of outer space. Thank you very much to Jane Sidell, Historic England’s Inspector of Ancient Monuments in the London Planning Team, and to Professor Robert Winston for sharing his picks. Do join us next time when we’ll be finding out how a 19th-century dairy maid changed modern medicine forever – fancy that! You can still vote for the places you find irreplaceable to be featured in a future episode of our history of England at HistoricEngland.org.uk/100places – that’s the number 100 Places. You can also join the conversation on Facebook and Twitter with the hashtag #100Places. We do love to hear from you so do get in touch. Make sure you rate, review and subscribe to this podcast and then you will never miss an episode. Thank you so much for joining me, Emma Barnett, and I’ll see you next time for another instalment of Irreplaceable: A History of England in 100 Places.

Voiceover:

Irreplaceable: A History of England in 100 Places is a podcast by Historic England. Sponsored by Ecclesiastical Insurance Group. When it feels irreplaceable, trust Ecclesiastical.

Historic England manages the National Heritage List for England.

Join us as we travel across England visiting well-known wonders and some lesser-known places on your doorstep - all of which have helped make this country what it is today.

Our website works best with the latest version of the browsers below, unfortunately your browser is not supported. Using an old browser means that some parts of our website might not work correctly.