The Enduring Benefit of a Victorian Legacy

By Dr Katy Layton-Jones, historian and historical consultant, University of Leicester and Victoria County Histories

Before the 1840s there were no public parks in Britain. There were narrow paved ‘walks’, pleasure gardens and private estate parks, but the nation lacked large urban green spaces that were open to all. This was due in part to the close proximity of the rural hinterland, which remained within walking distance of town centres well into the 19th century. However, as towns encroached on surrounding fields, urban populations found themselves increasingly divorced from the natural world and its attendant physical and psychological benefits. Campaigners and politicians such as Edwin Chadwick and Robert Peel perceived the negative implications of this process, prompting them to champion the creation of green spaces for the benefit of all.

The principles that underpinned the Victorian parks movement were rational, persuasive and enduring. After some early unsuccessful experiments with partially-private parks, such as Princes Park in Liverpool (1842), the premise of free access characterised the funding and management models for all the great municipal schemes. From Birkenhead Park (1847) to People’s Park, Halifax (1857), Cannon Hill Park, Birmingham (1873) and Victoria Park, Bristol (1880), the public were afforded the right to enter and enjoy expansive green spaces free of charge. This precept was widely and vocally endorsed. As one Liverpool newspaper exclaimed in 1870, ‘the park is for the people – the people should use it without let or hindrance’ (Porcupine, 1870, p.77).

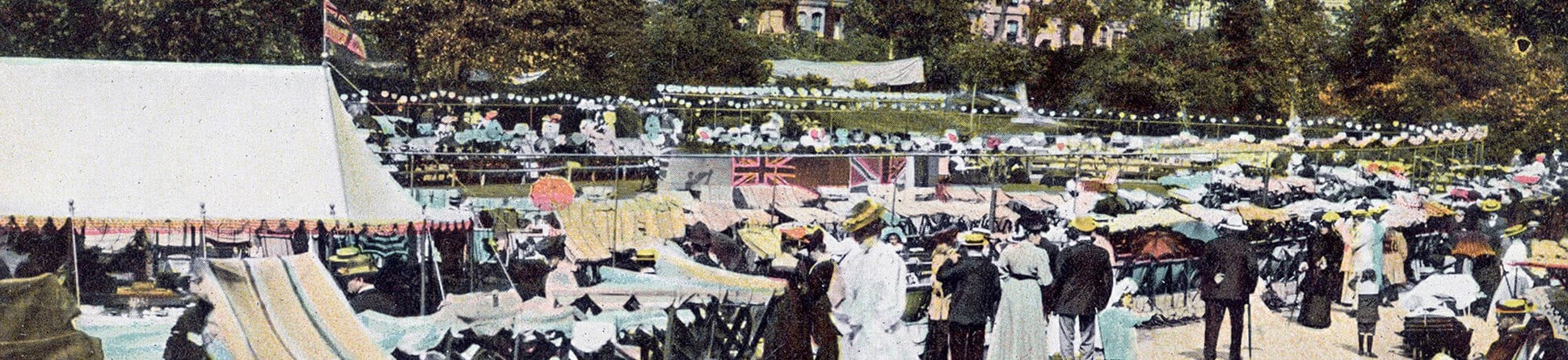

In addition to free entry, other universal characteristics emerged. Substantial areas of greensward became essential components of large parks. These facilities could be used for a wide variety of functions ranging from football to military drills, fancy fairs to dog walking. Alongside such adaptable spaces were ornamental lakes, naturalistic miniature woodlands, elaborate floral beds, and an increasing number of decorative and playful fountains and statues. Over the century that followed, children’s dells, cycle paths and glasshouses added to the attraction of public parks without challenging the egalitarian ethos of their creation.

Today, the public park is arguably the last bastion of the Victorian commitment to cultivate public good within the public realm. The enduring benefits of these flexible, accessible urban green spaces remain self-evident. The greensward that hosted cricket matches in the 1890s may continue to do so, but it might also be used for running, yoga, sketching, sleeping, reading, meditation, impromptu Frisbee and imaginative play. These landscapes yield to social change with little or no need for intervention or alteration. 150 years of public park provision has ensured that these historical landscapes have become integral to our social, intellectual and environmental infrastructure. Their ability to serve so many for so long testifies to the perennial nature of human needs and desires; to protect them is not merely an exercise in heritage preservation, but also and more importantly, a powerful reaffirmation of an enduring social contract.

References

‘Editorial’, The Porcupine, 21 May 1870, p.77

Please share and comment

Join the debate on Twitter: #parksmatter or send your responses to Sarah Tunnicliffe and share this article on social media via the tab on the left.