Nuns and Convent Building

The Catholic Relief Act of 1829 lifted an injunction on convents that had been in place since the Reformation and set the stage for a boom in convent building.

Many of these buildings were designed or adapted for a new type of Roman Catholic religious community, known as an 'active congregation'. Unlike earlier orders, in which nuns lived contemplative lives in enclosed convents, active sisters undertook work outside the convent. These women established schools, orphanages, care homes, hospitals and refuges.

The new convents had to meet a range of practical and modern needs and, though they often looked similar in style to their medieval predecessors, were very different in layout and use.

Women's religious communities were usually responsible for raising their own funds and managing their budgets and this, combined with the fact that only the sisters had a clear idea of how their buildings were to be used, meant that they had a great deal of control over the design and construction - a privilege that very few Victorian women shared.

The sisters commissioned their own architects, provided detailed design briefs, and sometimes drew up the plans themselves. Once the building work began, they were involved in every part of the construction process, from project managing the site to designing and decorating interiors (particularly chapels).

Far from being the places of oppression popularly portrayed in Victorian protestant culture, life in a convent could offer middle class women the freedom to learn and develop a wide range of skills and engage in public work - opportunities that were often denied to married women.

St Mary's Convent, Handsworth

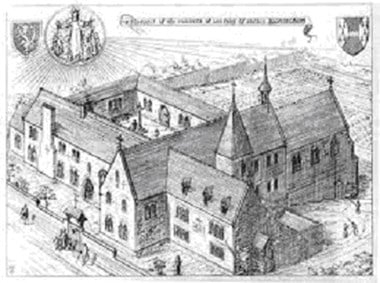

Designed for the Sisters of Mercy by A.W.N. Pugin, the convents of Our Lady of Mercy at Bermondsey and St Ethelreda's (now St Mary's) at Handsworth (1839 and 1841, respectively) were the first to be built in England in the 'Gothic' style, which would dominate ecclesiastical building for the rest of the century.

Together, they set many design standards for subsequent Catholic convents. The architect's brief for St Mary's Handsworth was drawn up by Catherine McAuley, foundress of the Sisters of Mercy, who had already overseen the building and adaptation of five convents in Ireland.

McAuley was extremely unhappy with the convent that Pugin designed at Bermondsey, which she regarded as being overly monastic in style and gave very precise instructions for Handsworth, from the layout and form of the building down to exact measurements for room sizes.

Mayfield School, Mayfield

Mayfield School (formerly convent) in East Sussex, a restored medieval bishop's palace, was the first pre-reformation building to be returned to Catholic use after the Relief Act.

The ruins of the palace were bought by Louisa Carroll, Duchess of Leeds and gifted to her friend Cornelia Connelly, foundress of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus, for use as a convent. In order to finance the restoration Connelly sent her nuns on a begging tour of Europe and, despite fierce resistance to the project from Bishop Thomas Grant, she finally raised sufficient money to commission E W Pugin.

The convent incorporated a school which pioneered Connelly's progressive education philosophy. Connelly, herself a trained artist, placed great emphasis on art and along with other sisters decorated parts of the convent. This tradition continues; some of the post-war buildings on the site were designed by Mother Mary Lorenzo Fitzgerald-Lombard, a trained architect.

St Marye's Convent, Portslade

St Marye's was established by the Congregation of the Poor Servants of the Mother of God (SMG) in 1904.

Like many congregations, The SMGs adapted an existing building which they extended as the community grew. Designs for the chapel, added in the 1930s, are thought to have been produced by the then Superior-General, Mother Mary Lucy Forrestal SMG.

The convent was initially founded as a refuge for 'penitents' and, as was generally the case with such institutions, ran a laundry which, together with a small farm, generated a modest income. The laundry built in 1908, still stands today, complete with drying racks and pulleys.

St Mary’s Convent, Brentford

St Mary's Convent in Brentford was one of the most important convents of the Congregation of the Poor Servants of the Mother of God (SMG). It operated as a 'central house of work', generating an income that helped support the smaller convents.

Like St Marye's, Portslade, the congregation adapted and added to an existing house which they first leased in 1880. As the local community regarded the congregation with suspicion (reflecting the strong vein of anti-Catholicism in wider Victorian society) Frances Taylor, foundress of the SMGs, had to conduct the negotiations to secure the building in secular dress.

The SMG archives reveal extremely detailed accounts of the successive building programmes at their convents, describing the disputes that arose between the building contractors, architects and sisters. Diary entries show the extent of knowledge that sisters acquired about the building process in order to ensure that the convent building was carried out exactly to their specifications.

Bibliography

- Armour, M.A., Blake, U., Dawson, A., Cornelia: The story of Cornelia Connelly (1809-1879) Foundress of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus. Society of the Holy Child Jesus, 1979

- Hill, R., God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. London: Allen Lane, 2007

- Leonard, Sr Eithne, Frances Taylor - Mother Magdalen 1832-1900 Servant of God. London: Catholic Truth Society, 2009

- Mangion, C., Contested Identities: Catholic women religious in nineteenth-century England and Wales. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008

- Pugin, A.W.N., The Present State of Ecclesiastical Architecture in England. London, 1843. Full text available at Google Books

- Shaw, P. St Mary's Convent, Brentford: A short history and guide to the convent and heritage rooms (draft) Internal SMG publication, 2007

- Sullivan, M.C. (ed.) The Correspondence of Catherine McAuley, 1818-1841. Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Four Courts, 2004

- Walsh, B., Roman Catholic Nuns in England and Wales 1800-1937. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2002

Archives

- Central Congregational Archive of the Poor Servants of the Mother of God, Brentford, Middlesex

- Society of the Holy Child Jesus Archives, Oxford

- General Archives of the Union of the Sisters of Mercy of Great Britain, Handsworth, Birmingham

Public Access

- St Mary's Convent, Handsworth - open to the public for guided tours

- St Marye's Convent Portslade (now Emmaus Brighton and Hove) - open to the public

- St Mary's Convent, Brentford Open to the public currently only through the annual open days - Open House London - organised by Open City

- Mayfield School, Mayfield, East Sussex - Not open to the public

A.W.N. Pugin (1812-1852)

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin was the son of a French émigré architect. Although he was raised a protestant, he converted to Roman Catholicism - a move that significantly influenced his ideas about ecclesiastical architecture.

Pugin redeveloped the Gothic style that had been gaining popularity from the late eighteenth century, shifting the emphasis from romantic to spiritual. He published several treatises on church building and his strict adherence to the Gothic style is demonstrated by his commitment to precisely reproduce historical models rather than create new ones.

Throughout his short career, Pugin designed over fifty churches and religious institutions. Ironically, he is probably best known for his work on the Houses of Parliament; a building to which he contributed relatively little (the overall design is credited to Charles Barry). Pugin suffered mental health problems in later life and in 1852 was committed to the infamous asylum, Bedlam. By the time he died, aged only 40, he had established himself as the leading Gothic architect.

E.W. Pugin (1834-1875)

At 18, A.W.N's son, Edward Welby Pugin, found himself in charge of his father's offices in London, Ramsgate, and Liverpool. Most commissions continued to be from the Catholic Church and, like his father, Edward was driven and prolific - in England alone, he designed at least forty religious buildings.

Although he was dedicated to the Gothic style, his interpretation of it was rather looser than A.W.N's, and his architecture is regarded as more eclectic. Throughout his career, he formed partnerships with several well-known Catholic architects including J. A. Hansom, and in Ireland, he established a successful practice with his brother-in-law, George Ashlin. These relatively short-lived partnerships, however, were probably blighted by Pugin's notoriously quarrelsome temperament.

His later years were dogged by controversy - legal action was brought against him on two occasions, once for libel in 1870 and again for perjury in 1874 and his membership of RIBA was withdrawn. After his death, the family business was continued, with less success, by his brother, Peter Paul, and half-brother Cuthbert Pugin.

Kate Jordan is writing her PhD at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, on the role of nuns in convent building.

Nuns and Convent Building

Please click on the gallery images to enlarge.