Specialist Education for Children with Disabilities: 'The Happiest Effect'

This section tells you about some of the inspirational blind and deaf people who fought for the right for children with disabilities to be educated. These people illustrated what disabled children with an education could achieve.

In this section

Audio version: 🔊 Listen to this page and others in 'Disability from 1660 to 1832' as an MP3

Disabled children excluded from education

In the first half of the 18th century, the thriving charity schools movement that provided education for the children of the poor did not include children with disabilities. Those from better-off families could enjoy private tutoring or take their chance in mainstream school, but the disabled children of the poor were unlikely to receive an education.

Thomas Arrowsmith, deaf artist

In Gloucestershire, Thomas Arrowsmith (1771-c1830) was born deaf. At the age of four or five, he was taken to the local village school by his mother where she demanded that he be educated. Despite the misgivings of the teacher, he was admitted and did well. He eventually became a pupil in England's first special educational provision for the deaf - Braidwood's Academy for the Deaf and Dumb in Grove House, Hackney on the eastern edge of London.

Thomas went on to become a well-known painter, studying and exhibiting at the Royal Academy. He was the first of a number of distinguished graduates of the Braidwood Academy.

The Braidwood Academy

Thomas Braidwood (1715-1806) set up his academy in London in 1783 having run a successful school in Edinburgh since 1760. He used a form of sign language known as the 'combined' system (later known as the 'Braidwoodian' system) which later developed into British Sign Language.

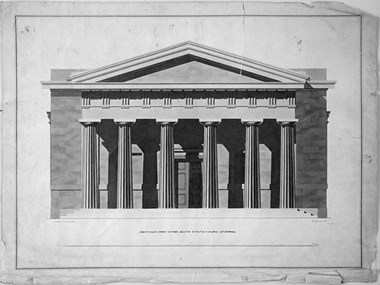

Braidwood had dreamed of setting up a public school for poor deaf children. However, it was one of his pupils, John Creasy (c1774-1855), who inspired and persuaded his local clergyman to raise money to build the London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb in Bermondsey in 1792. This was the first ever public school for the deaf in England. A former pupil, William Hunter (1785-1861), later became Britain's first deaf teacher of the deaf. According to the head teacher this had "the happiest effect" of a deaf teacher communicating with deaf pupils in their own manner.

The radical Edward Rushton

Meanwhile, a young man from Liverpool, Edward Rushton (1756-1814), survived sinking on a ship that was transporting enslaved Africans to Dominica. Outraged at the brutal treatment of the enslaved people on the ship, he was charged with mutiny after remonstrating with the captain. He had tried to help the captives by giving them food and water. Many of them had caught the highly contagious ophthalmia and he contracted the disease himself, losing the sight in one eye and becoming virtually blind in the other.

On his return he became a poet, a campaigner for the abolition of the trade in enslaved people, a newspaper editor and general supporter of radical causes.

The Liverpool School

Rushton's most lasting legacy was the Liverpool School for the Indigent Blind in London Road which opened in 1791. It was the first specialist school for the blind in the country, second in the world after Paris.

Pupils were taught music, weaving, basket making, spinning and other trades to equip them for economic survival and independence after school. The school survives today (in a new location) as the Liverpool Royal School for the Blind. Inspired by Rushton, blind schools were built in Bristol (1793), London (1799) and Norwich (1805).

Watch the BSL video on specialist education for children with disabilities

Specialist Education

Please click on the gallery images to enlarge.