Back to the Community: Disability Equality, Rights and Inclusion

This section describes the struggle for disability equality, rights and inclusion which began in earnest after the Second World War, and which led to the end of the asylum and the policy of 'care in the community'.

In this section

Audio version: 🔊 Listen to this page and others in 'Disability Since 1945' as an MP3

The start of the new militancy

In 1946, the National Cripples Journal denounced the government's promise of "security from cradle to grave", claiming that it did nothing for "the civilian cripple, who is incapable of earning a living". If there was going to be a bold new society fit for all, disabled people must be a part of that 'all'.

Parents and family-led organisations

Many new campaigning organisations sprang up, at first led by parents and families. In 1946 the National Association for Mental Health, and the National Association of Parents of Backward Children were formed, later becoming MIND and Mencap respectively. The Leonard Cheshire Foundation, British Epilepsy Association, the Spastics Society (now Scope) and hundreds of others soon followed.

Campaigns by disabled people

Disabled people themselves began to campaign. In 1951, 800 members of the British Limbless Ex-Servicemen's Association took part in a 'silent reproach' march to 10 Downing Street.

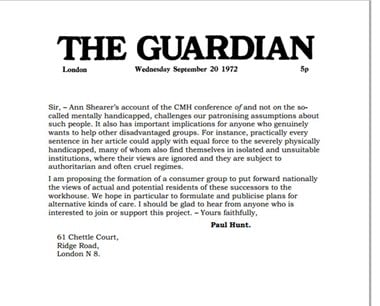

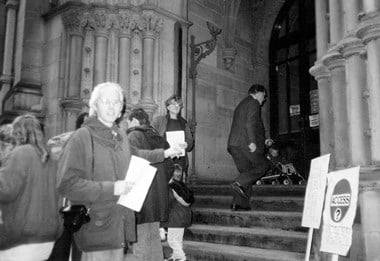

Then in the 1970s and 1980s, campaigning organisations of disabled people came to the fore - the Union of the Physically Impaired against Segregation (UPIAS), the Mental Patients Union (MPU) and, for people with learning disabilities, People First.

Disabled MPs

Two wounded First World War veterans who both entered Parliament, the double amputee Jack Brunel-Cohen (Liverpool Fairfield) and the blinded Ian Fraser (Morecambe and Lonsdale, Lancaster) fought for disabled ex-servicemen's rights. The deaf MP Jack Ashley (Stoke on Trent South) campaigned for the rights of disabled people generally.

A new 'social model' of disability

In 1968, the American academic Wolf Wolfensberger (1934-2011) denounced asylums and long-stay hospitals as abusive institutions - their design and their routines dehumanised people. From the 1970s, disabled campaigners such as the sociologist Michael Oliver and disability studies pioneer Vic Finkelstein (1938-2011) at the Open University in Milton Keynes advocated the social model of disability. In this model, disabled people control their own lives, challenging non-disabled society.

Tara Flood, Paralympic swimmer and Director of the Alliance for Inclusive Education (ALLFIE), has spoken of the importance of the social model for disabled people as part of the How was school? project.

Public disquiet

After the Second World War, long-stay hospitals for people with learning disabilities and mental illness seemed neglected and forgotten. From the 1960s, abuse scandals erupted onto newspaper front pages, triggering enquiries at Ely Hospital in Cardiff; Farleigh Hospital in Flax Bourton, North Somerset, and Coldharbour Hospital in Sherborne, Dorset.

A famous television documentary, 'Silent Minority', exposed further scandals at St Lawrence's in Caterham, Surrey (also known as Caterham Lunatic Asylum for Safe Lunatics and Imbeciles) and Borocourt in Reading, Berkshire. Public disquiet became overwhelming.

'Care in the Community'

The 1981 Care in the Community Green Paper signalled the end of the asylum. Over the following two decades, tens of thousands of people moved back to the community from the hospitals. A new era of residential and group homes, day-care facilities and independent living within mainstream communities began.

ALLFIE have created a video archive, How was school?, containing interviews with disabled people on their experiences; themes include experiences within mainstream schools and the expectations people had of disabled children.

21st century ideas

Thinking continues to evolve. In the new century, ideas of empowerment and self-direction have taken the lead in which disabled people acquire a personal budget to buy support, rather than 'receive' care. The idea of specialist homes and buildings is challenged - many believe there should be 'universal design' for 'universal buildings'.

We find ourselves at the end of the asylum period, an era which only represents 140 years of disability history, and which never involved all disabled people. But the long shadow of Bedlam remains. How will places for people with disabilities develop in the future?

Watch the BSL video on disability equality, rights and inclusion

Back to the Community

Please click on the gallery images to enlarge.